I have seen several remarkable performances of Coriolanus. Two stand out in my memory. Ian McKellen took on the role at The National Theatre in 1984. I remember it as a blood-soaked staging, and the picture below seems to confirm that.

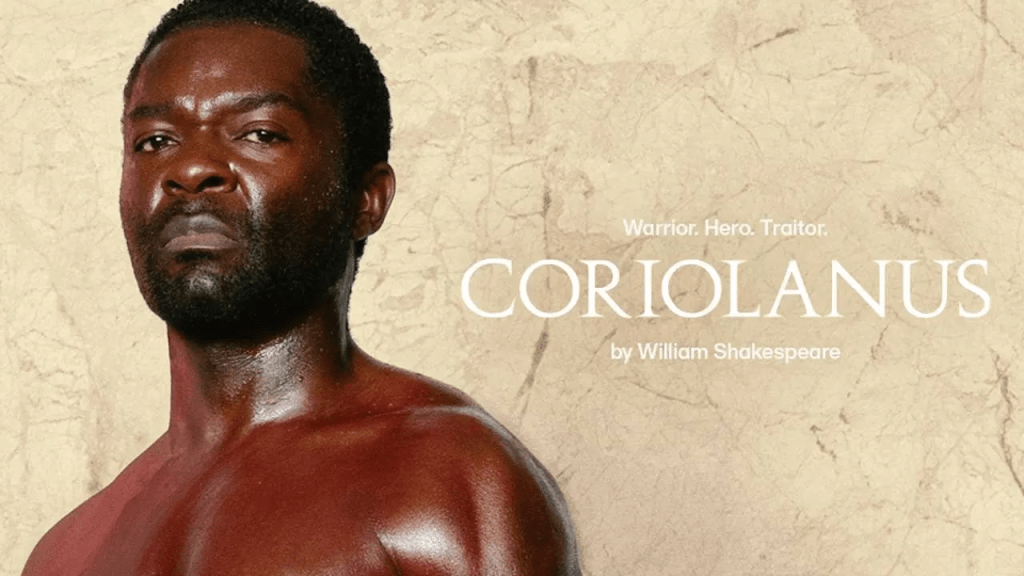

More than fifteen years later, I saw Ralph Fiennes play the part of the arrogant Roman in a darker, more psychologically intense staging at (I think) the Gainsborough Studios in London. It has always been one of my favorite Shakespeare plays, so I was excited to head back to The National Theatre recently to see how David Oyelowo would interpret the role. The production was still in preview, so the cast was still working out the kinks. (Oyelowo forgot his lines at one point, but recovered after a nerve-racking moment). Overall, it struck me as a cinematic, polished, and slightly flashy staging. It felt a little muddled in design terms. Generals brief their battlefield commanders via cell phones and video calls while soldiers fight with swords and shields. The action moves from sleek, expensive, hotel-style interiors to unadorned public spaces staged like a museum. Performances were generally very strong.

Coriolanus is very much a play for our times. Politicians inflated with hubris and boastfulness, pretending to care for the people when it suits, but otherwise deeply contemptuous of them, and fickle, easily. manipulated electors. Does any of that sound familiar or urgently relevant to our times?