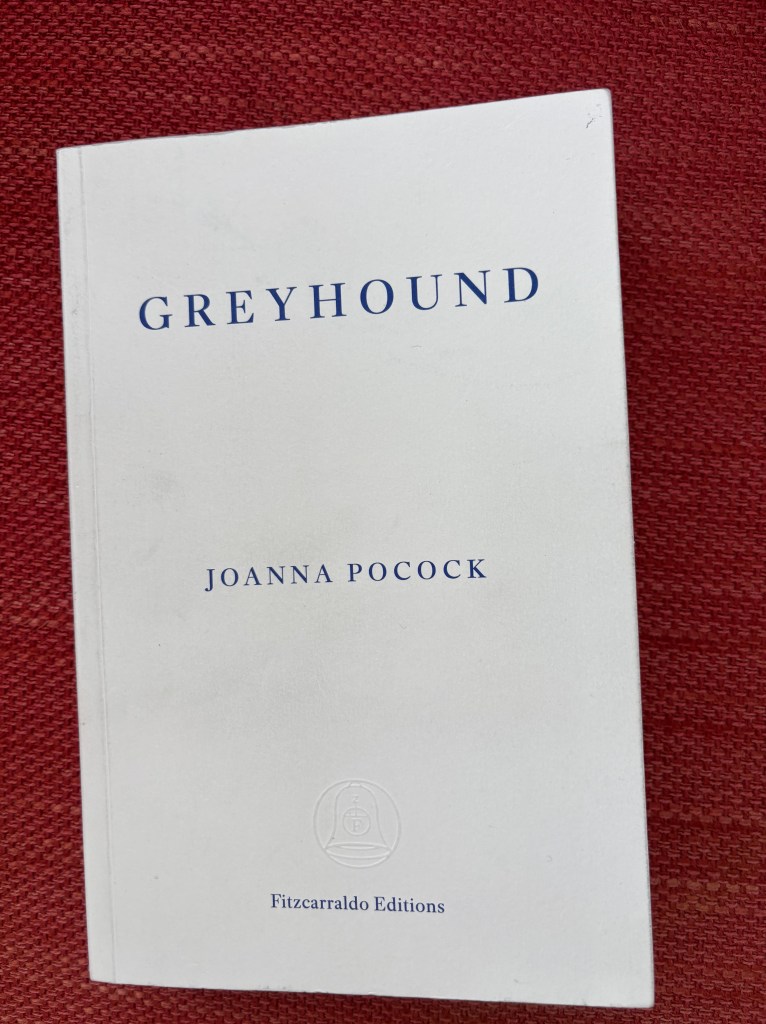

The cross-country American road trip has fascinated many great writers. Most of them have been men and most of them have completed the trip by car. Joanna Pocock, a Canadian-born writer, did it differently, traveling from Detroit to Los Angeles by Greyhound bus. She did it first in 2006, taking to the road in the wake of personal tragedies including the loss of her sister and several miscarriages. She repeated the road trip in 2023, making Greyhound in part a sustained reflection of how America has changed in the intervening years. It is a brilliant and fascinating book; grim reading for sure and shot though with sadness and despair for the state of the nation. It is also a compelling and depressing account of the environmental devastation underpinning so much of American “progress”.

Pocock has immersed herself in the literary canon and I enjoyed learning about writers I was previously unfamiliar with such as James Rorty.

“I encountered nothing in 15,000 miles of travel that disgusted and appalled me so much as this American addiction to make believe. Apparently, not even empty bellies can cure it. Of all the facts I dug up, none seemed so significant or so dangerous as the overwhelming fact of our lazy, irresponsible, adolescent inability to face the truth or tell it.”

Pocock has written a thoughtful account of modern-day America and a poignant elegy for a country that many feel has lost its way and betrayed its founding vision.