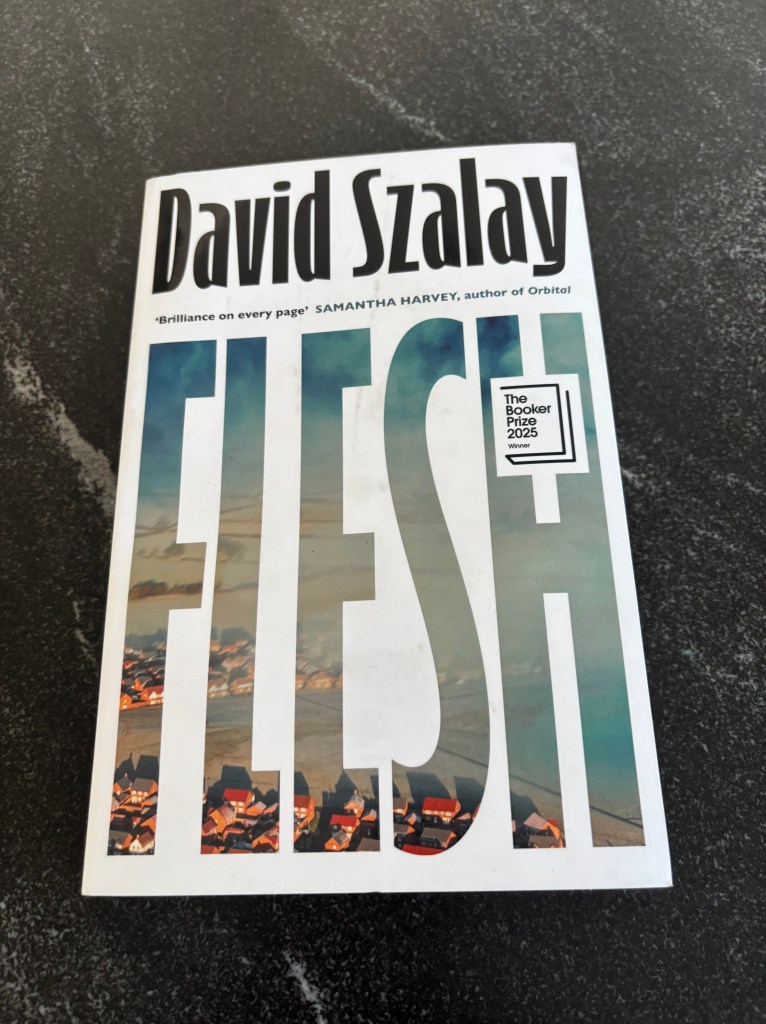

Flesh, which won the Booker Prize in 2025, tells the story of Istvan. Born in a small town in Hungary, Istvan moves, after a spell in a juvenile prison and some time serving in the Hungarian army, to London where he takes a dead end job as a security guard at a strip club. A moment of selflessness and courage changes the course of his life, taking him into the world of a wealthy businessman. That’s probably enough about the plot because I don’t want to spoil anyone’s enjoyment of an unusual and powerful novel.

The story is a simple enough one. What distinguishes Flesh is its remarkably spare and pared back prose. There is scarcely a wasted word and there is a cool precision to the writing that complements perfectly Istvan’s emotional detachment and the difficulty he has connecting with people and with difficult experiences. Istvan encounters tragedy, success, wealth, and intimacy, yet finds himself towards the end of his life close to the place it all started and without the transformations that he might have expected for all his experience. Flesh is a brilliant accomplishment and well deserves all the accolades it has received.