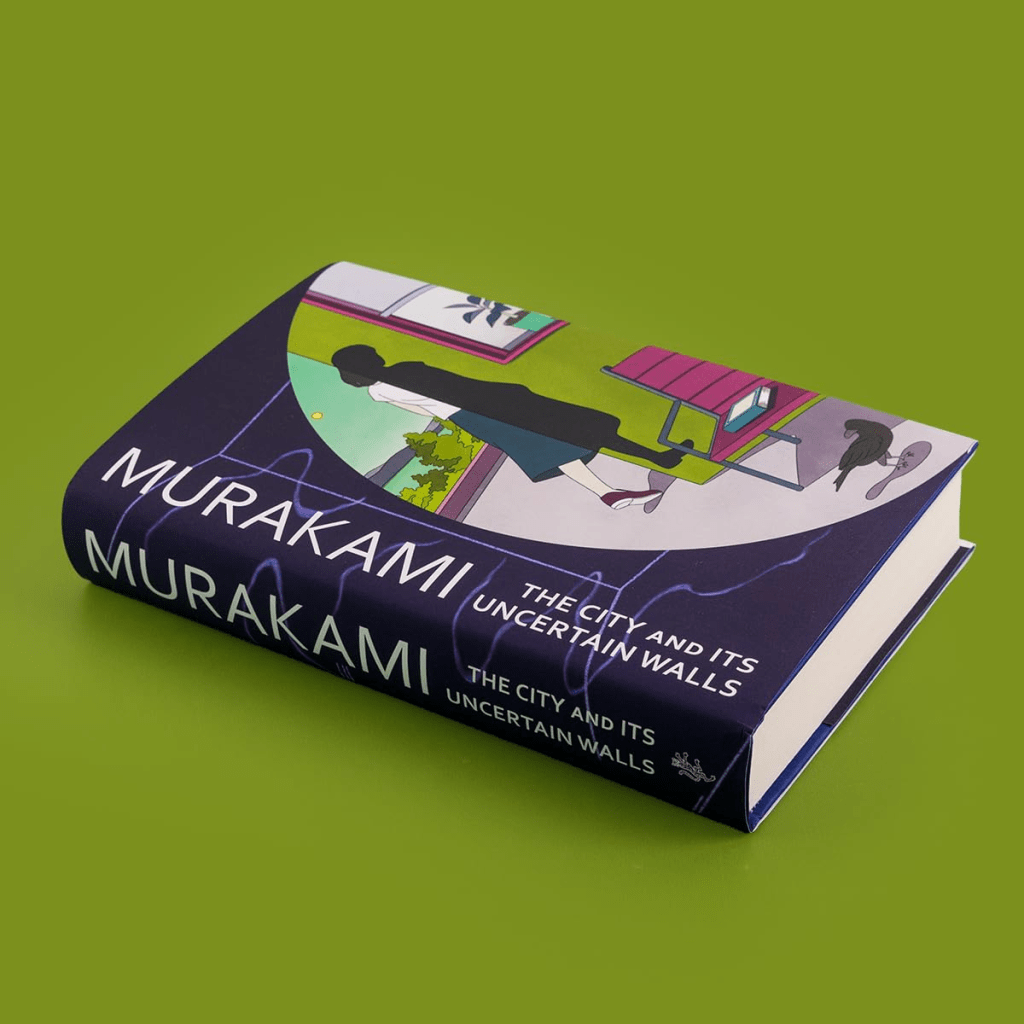

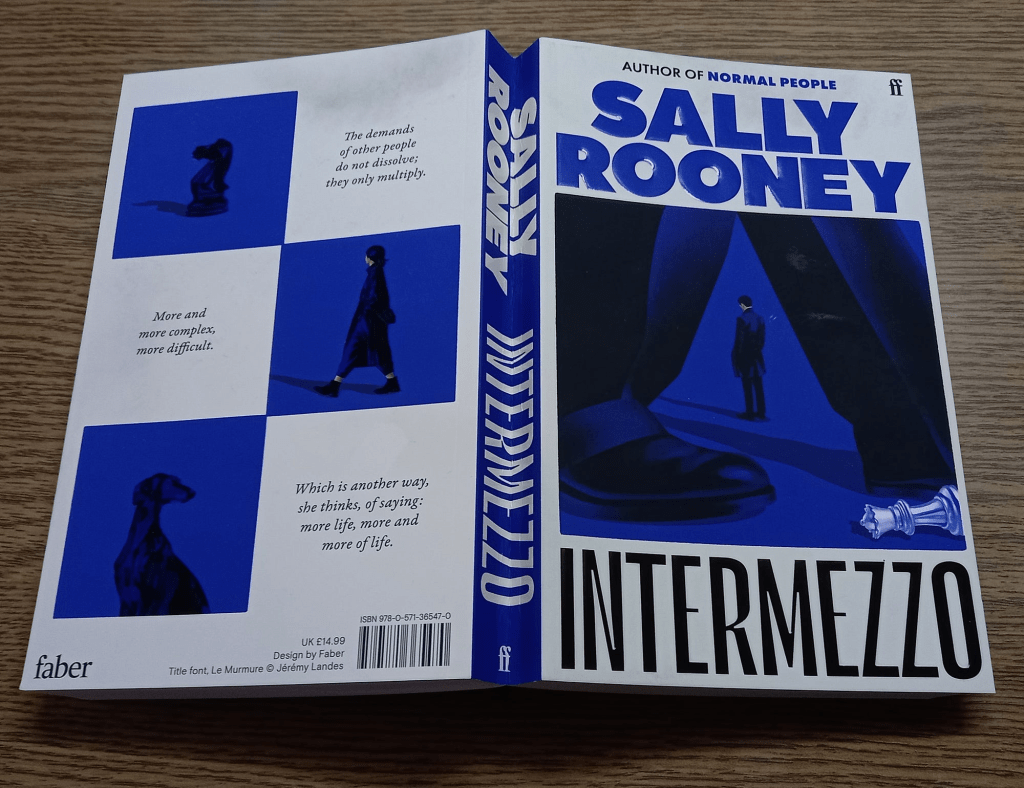

I finally got around to reading a novel by Sally Rooney. There is no obvious explanation of why it took me so long. Huge sales, well received TV adaptations, and all the critical plaudits a young novelist could hope to attract turned Rooney into a literary sensation quite some time ago. I caught up with everyone else just recently and completed her most recent book, Intermezzo. It’s very good.

Intermezzo tells the tale of two very different brothers. Peter, the eldest, is a successful lawyer in Dublin. Socially fluent, accomplished, and intellectual, he’s a conventional success story, at least on the surface. Closer inspection reveals the flaws. The insecurities, the grief following his father’s recent death, and the inability to settle, are masked by drug taking, but he’s not fooling anyone. Ivan, ten years younger, is a competitive chess player, once expected to get to the very top, but now plagued by doubts. He’s socially inept, shy, and nerdy. Each is offered the prospect of salvation through the love of good women (two good women in Peter’s case).

Not much happens by way of a plot. The brilliance of this novel lies in the exposure of Peter’s and Ivan’s interior lives and their troubled relationship. I can’t remember when I was last so impressed by a novelist’s skill at dialogue, or by the uncovering of those interior monologues we all deploy to make sense of our own and others’ experience. It’s all so utterly convincing. The climax of the novel is deeply impressive – truthful and authentic. Strange to say, but I now feel slightly reluctant to read Rooney’s earlier books in case they are not as good as Intermezzo.