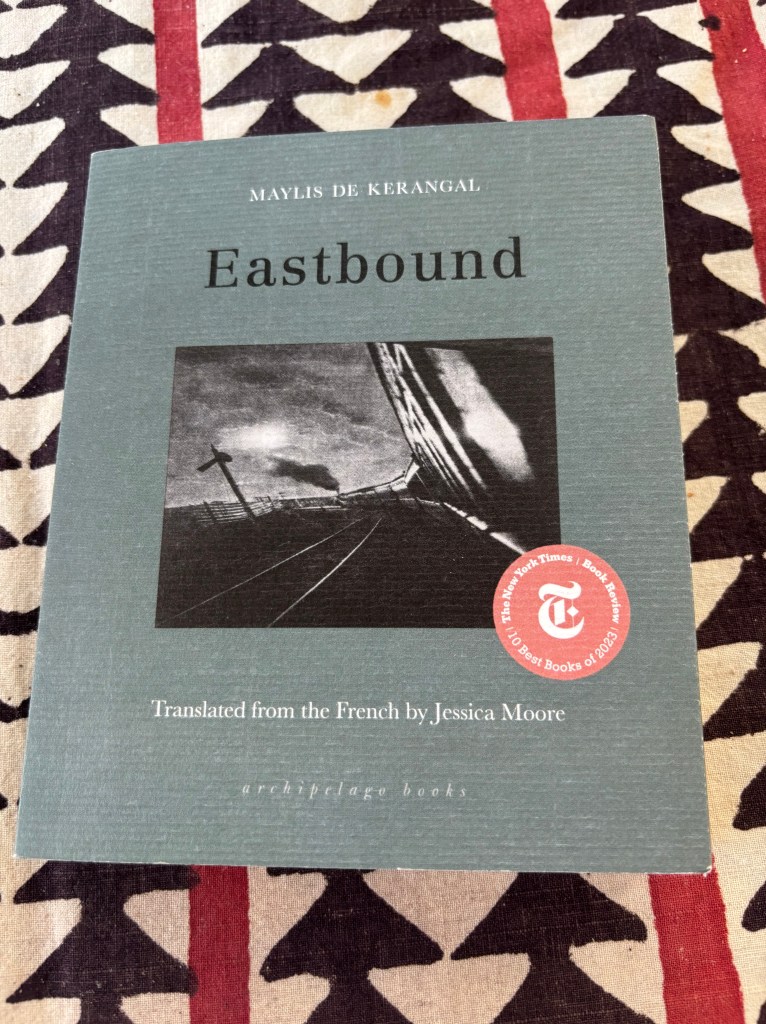

Most books are published in a relatively small number of standard sizes. While there are good reasons for that, titles published in unusual formats or with distinctive designs have a good chance of standing out among the thousands of similar looking books stocked by the average bookstore. Imaginative publishers know that. Browsing one evening recently in a fairly undistinguished chain bookshop in a Massachusetts mall, my eye was caught by a small, almost square paperback called Eastbound by Maylis de Kerangal. No doubt it was the unusual format and pared down, minimalist design that made me pick it off the shelf.

Eastbound features Aliocha, a young Russian conscript on his way to report for compulsory military service in Siberia. Traveling on the Trans-Siberian Express, Aliocha is so frightened of what lies at the end of the long journey that he is determined to abscond. On the train he meets Helene, a French tourist traveling in first class, and sees an opportunity to escape.

It may seem an implausible tale, but the author (Maylis de Kerangal) creates such an intense and dreamlike atmosphere on board the cramped and claustrophobic train moving relentlessly towards the frozen wastelands of Siberia that it hardly seems to matter. This is a novella about shared humanity, people’s destinies and fates and how they intertwine in the least likely of circumstances. Fevered and almost surreal, Eastbound may be short but it sticks in the memory.