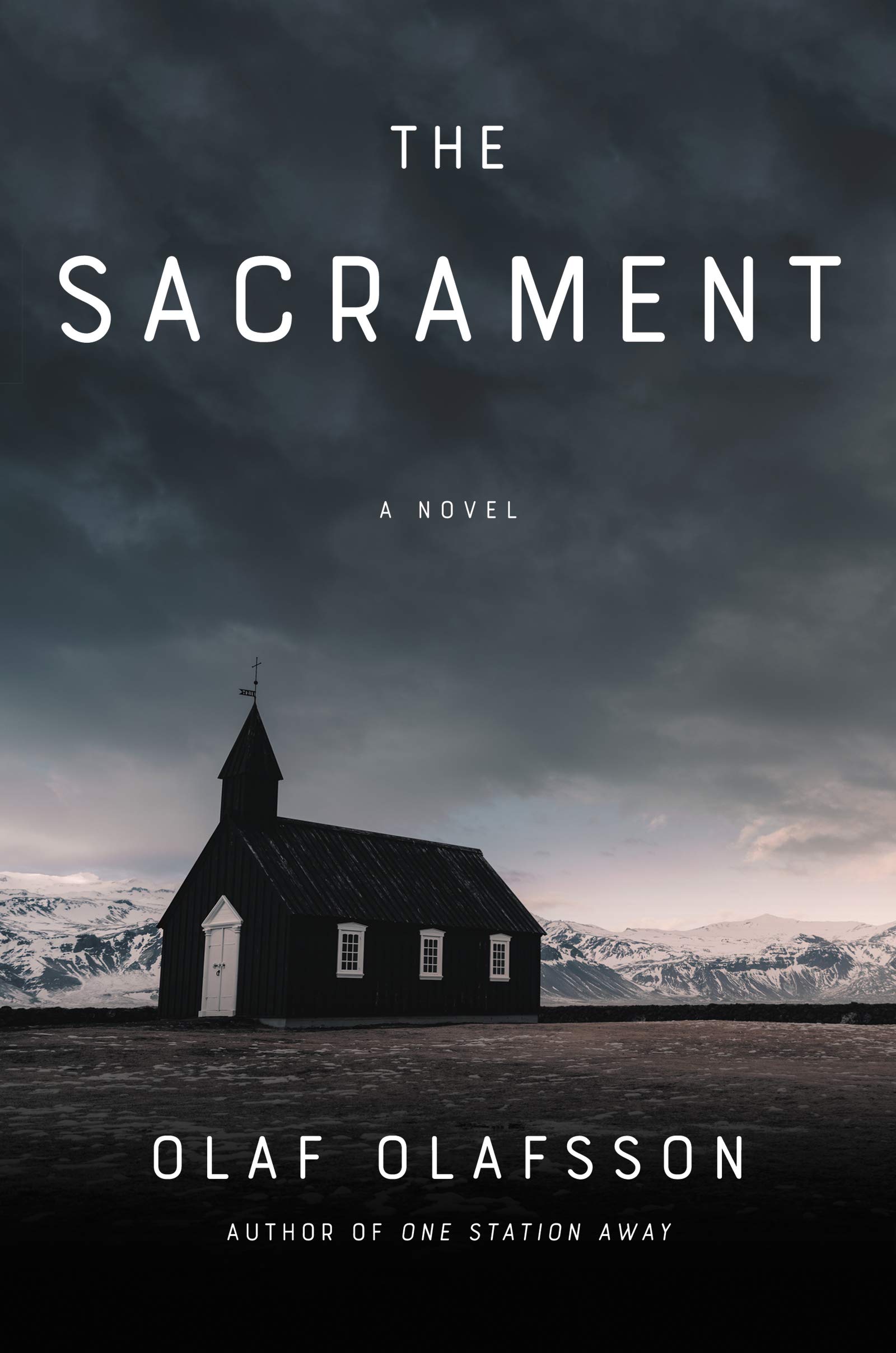

The hideous abuse of children by Catholic clergymen and its concealment by the Church’s authorities continue to appall the world. One scandal has followed another, leaving many innocent believers with their faith in tatters and asking how their belief in an all-loving God can be sustained in the face of such systematic evil. Olav Olafsson’s latest novel, The Sacrament, approaches the question through the experiences of a nun sent to Iceland by The Vatican to investigate allegations of abuse in a Catholic school. The mission she’s given pulls her from the quiet, sequestered life of a convent in France, a life marked by simple routine, a life lived in a community, a chapel and a rose garden. Her visits to Iceland, separated by decades, bring her into touch not simply with individual and institutional evil. She’s also forced to confront her past and the terrible decisions she made as a young student in Paris, choosing security, fear, and shame over the possibility of love.

The Sacrament isn’t a perfect novel, but its accomplishments are significant. The atmosphere it creates through simple storytelling is striking and long-lasting. Olafsson creates a world in which one voice, clear but uncertain, speaks for the tens of thousands left voiceless by the cruelty and ambition of the powerful few.