The history of black Britons wasn’t part of the curriculum when I was growing up in London. The history I remember learning in school – the causes of the first world war, Russia in the nineteenth century and so on – now seems to me to have been chosen precisely because it had nothing to do with me or my classmates. We were black and white: Irish, Indian, Pakistani, Jamaican, and Italian, mostly born to immigrant families. What did the fate of the Romanovs have to do with us? Nothing. That was the point. It was equally irrelevant to all of us.

Later I learned of the arrival of Caribbean immigrants in 1948 to help re-build post-war London and saw the influx of South Asians following the crisis in Uganda in the 1970s. Even then no one taught me that black men and women had been part of British life for hundreds of years, that there had been black Londoners long before The Windrush docked. I knew nothing of the histories of my black friends and neither did they. I wish I had seen then the wonderful exhibition of photographs at the National Portrait Gallery in London that I saw recently.

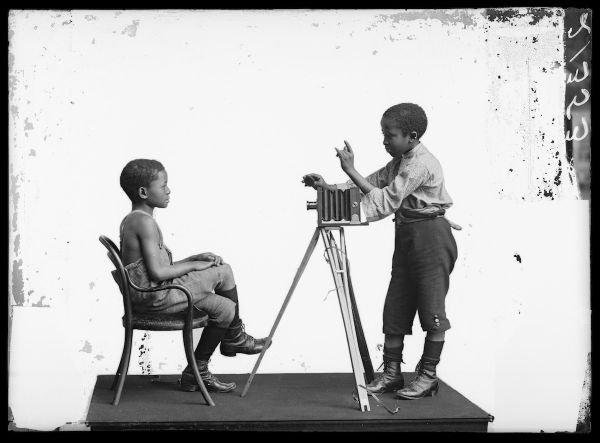

Black Chronicles shows more than forty photographs from the NPG’s own collection and the Hulton Archive. New, large prints made from the original negatives portray black politicians, musicians, dignitaries and dancers from as early as 1862. Many of the portraits are beautiful, but the exhibition does much more than bring together a set of striking images. It did something my history teachers should have done more often: it taught me something important about where I was born.