Back in 1983 Granta dedicated an issue of the magazine to the Best of Young British Novelists. Almost all the authors featured have lasted the course and, more than thirty years later, some of them – Julian Barnes, Kazuo Ishiguro, Ian McEwan for example – have matured into outstanding writers. Graham Swift was on the list. Many years later he won the Booker prize for Last Orders, so he’s hardly unknown, but he hasn’t attracted the wide readership and huge sales of some of his contemporaries. He isn’t especially prolific – I counted thirteen books in thirty-six years – and his work is more difficult to classify than his more famous peers, but I think he’s a better writer than almost all of them and one of a handful whose books I always buy as soon as they’re published.

Swift’s latest book is that rare thing – a novella. Too short to be novels, too long to be short stories, novellas seem to have gone out of fashion. Whether that’s because publishers discourage or dislike them (it’s tough to charge the price of a novel for something only a hundred pages or so long), or because it’s too challenging a form for most writers, I’m not sure. It seems to suit certain writers: the careful and precise, those who weigh every word, those sensitive to the pace and rhythm of every sentence.

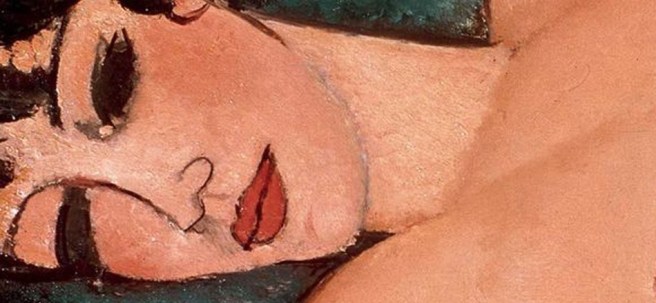

In Mothering Sunday, Jane Fairchild, celebrated novelist, looks back from old age to one momentous day in 1924 when she was a housemaid. On the surface, it could hardly be a simpler story: a recollection of a few stolen hours with her middle class, soon-to-be married lover, Paul Sheringham. She lies in bed one March morning, watching her lover get dressed before he leaves to join his fiancee for lunch, and then wanders naked and alone through his deserted house. Simple, but in little more than a hundred pages, Swift gives us an entire world. A world just emerging from the first world war but already preparing for the second. A world of crumbling social norms and structures, a world dying quickly but unpredictably. As Jane the housemaid, rising from her lover’s bed, sticky from sex and contraceptive cap still in place, moves naked through the empty house (the type of place she’s paid to clean), looking at paintings, touching dusty books, you feel not just an individual life on the brink of change, but a whole world. The world of Paul and his kind is dying and out of its ashes a new one is emerging, one that will be claimed and shaped not by men and the former masters but by women and the sharp, strong, and confident servants like Jane.

This is an exquisite book, one that I can imagine reading over and over again in the future. I loved every line of it. How often can you say that?